Evolution of SCSI: How Storage Interfaces Have Changed

If you’ve ever struggled with a tangled nest of thick cables behind an old server rack or spent an afternoon troubleshooting why a tape drive suddenly “disappeared” from your system, you have probably met SCSI, the storage interface that built the backbone of enterprise computing for decades.

SCSI – Small Computer System Interface, isn’t just a relic. It’s a story about standardization, scalability, and the quiet revolution that made modern data centers possible. And while you might not be installing a PCI SCSI controller today, the fingerprints of SCSI are all over your SAS drives, your NVMe arrays, and even your cloud storage architecture.

So, let’s rewind a bit, not to bury SCSI, but to understand why it mattered, how it evolved, and what its journey teaches us about the tech we rely on now.

The Problem SCSI Solved – And Why It Felt Like Magic

Back in the early 1980s, connecting peripherals was a mess. Your printer might not talk to your hard drive. Your scanner could be locked to one brand. Everything used proprietary interfaces, which meant vendor lock-in was the norm, and flexibility was a dream.

Then came SCSI.

For the first time, you could plug a SCSI hard drive, a CD-ROM drive, a tape drive, and even a printer into the same system using a common language, such as the SCSI protocol. It wasn’t just about storage; it was about interoperability.

The original SCSI-1 standard (ratified in 1986) supported 5 MB/s over a parallel bus, used a 50-pin connector, and allowed up to eight devices on a single chain. Devices were linked in a daisy-chain configuration, saving precious space in crowded server rooms. But this clever setup came with a catch: termination.

SCSI terminators: Without active or passive terminator plugs at both ends of the SCSI bus, electrical signals would bounce back like echoes in a canyon, corrupting data or crashing the whole system. Miss one tiny plug? Say goodbye to your storage array. Ask any sysadmin from the ’90s; they have been there.

Iterative Refinement: The SCSI Standard Advances

SCSI evolved rapidly to meet growing demands for speed, capacity, and reliability. Each revision built upon the last while preserving backward compatibility, enabling organizations to extend the life of existing investments.

- SCSI-2 added support for wider data paths (hello, Wide SCSI), faster clock speeds (Fast SCSI), and a richer command set that improved device compatibility.

- Combine them? You got Fast Wide SCSI, a major leap in throughput.

- Ultra SCSI pushed speeds to 20 MB/s and introduced 68-pin high-density connectors.

- Ultra2 SCSI brought Low-Voltage Differential (LVD) signalling, allowing cable runs up to 12 meters with cleaner signals.

- Then came Ultra3 SCSI, also known as Ultra160 SCSI, which achieved 160 MB/s, introduced tagged command queuing (TCQ) for smarter I/O, and used CRC-based error detection for unwavering reliability.

Each version kept backward compatibility, so you could (theoretically) plug an old SCSI-1 scanner into a shiny new Ultra160 controller. In practice? You’d run at the speed of the slowest device, but at least it worked.

This was huge for businesses. Instead of replacing entire systems, they could scale storage incrementally, a lifeline for growing data centers and server environments.

The Hardware That Made It Work

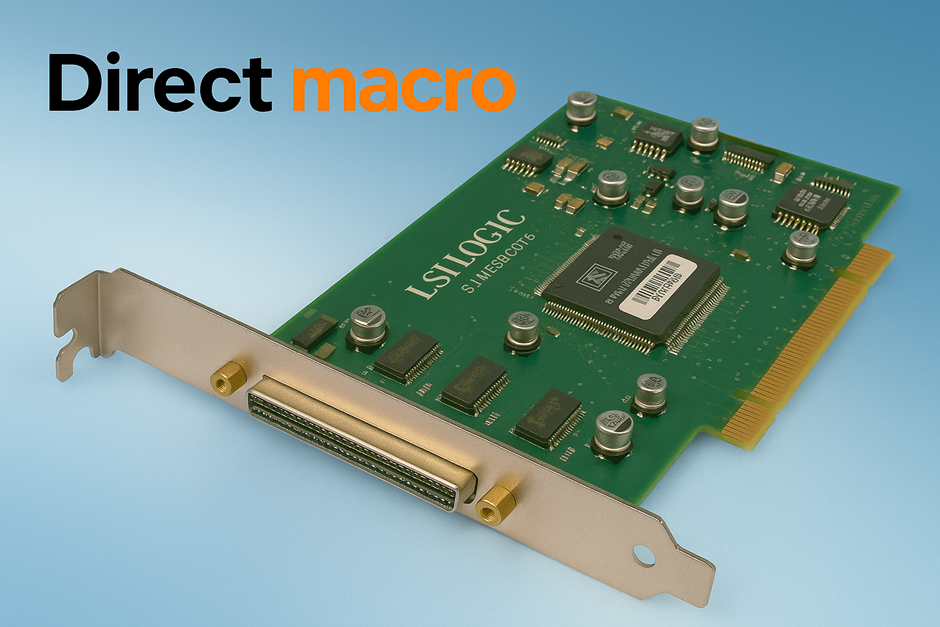

None of this happened without the unsung hero: the SCSI controller.

Also known as a host bus adapter (HBA), SCSI host adapter, or SCSI interface card, this expansion card sat between your CPU and your storage devices. Early PCs used ISA SCSI controllers; later, PCI SCSI controllers offered better bus mastering and arbitration. Eventually, PCIe SCSI controllers delivered the bandwidth needed for high-end RAID arrays.

These controller cards managed everything: assigning SCSI IDs, handling LUNs (Logical Unit Numbers), and ensuring smooth communication across the SCSI bus. In enterprise setups, Ultra320 controllers powered mission-critical disk arrays, often using differential SCSI (either LVD or the rarer HVD) for maximum reliability.

But let’s be honest: cabling was a nightmare. SCSI cables were thick, stiff, and came in different models, single-ended for short runs and differential for long ones. Get the pin configuration wrong, or exceed the maximum cable length, and you’d spend hours chasing ghosts in your logs.

The Rise of Competitive Interfaces

Despite its strengths, SCSI faced mounting pressure from simpler, lower-cost alternatives.

IDE (Integrated Drive Electronics), later Parallel ATA, offered a cheaper, simpler alternative for desktops. No terminators. No IDs. Just plug and play. It lacked SCSI’s multi-device elegance, but for most users, that was fine.

Then Serial ATA (SATA) arrived in the early 2000s. With serial connections, thin cables, and one-drive-per-port simplicity, SATA killed the need for daisy-chaining, SCSI IDs, and termination altogether. Suddenly, storage was easy and cheap.

Meanwhile, Fiber Channel took over high-end storage area networks (SANs), offering speeds far beyond parallel SCSI and clean scalable storage for large enterprises.

But SCSI wasn’t done yet.

Serial Attached SCSI (SAS) emerged as the best of both worlds: the reliability, command queuing, and enterprise-grade features of SCSI, combined with the serial architecture of SATA. Today, SAS controllers still power servers where uptime matters more than cost and they can even host SATA drives, thanks to backward compatibility.

And now? NVMe over PCIe delivers gigabytes per second of throughput, leaving even Ultra320 SCSI’s 320 MB/s in the dust. Meanwhile, Ethernet-based storage (like iSCSI or NAS) has made dedicated SCSI buses largely obsolete.

Why SCSI Still Matters, Even If You Don’t Use It

You might not be installing a 68-pin SCSI connector today, but SCSI’s legacy lives on.

- The SCSI command set is still used in SAS, USB mass storage, and even some NVMe implementations.

- Concepts like LUNs, bus arbitration, and tagged command queuing shaped how modern storage handles multiple requests.

- Most importantly, SCSI proved that open standards beat proprietary silos, a lesson that echoes in today’s push for interoperability in cloud and AI infrastructure.

And let’s not forget: plenty of legacy systems still hum along on SCSI. Industrial machines, medical scanners, and broadcast equipment work fine, and replacing them isn’t worth the cost or risk. For those teams, understanding SCSI settings, jumper configurations, and cable compatibility isn’t nostalgia, it’s daily reality.

Strategic Lessons from SCSI’s Evolution

- Standards unlock innovation. SCSI’s open nature let vendors compete on quality, not lock-in.

- Legacy support has hidden costs. Keeping old SCSI subsystems running might save money today, but at the price of flexibility tomorrow.

- Paradigm shifts follow steady progress. Serial interfaces overtook SCSI after 20 years of incremental improvement. The same thing’s happening now with NVMe and CXL.

Final Thought

The evolution of SCSI isn’t just a tech history lesson. It is a mirror for today’s decisions. Every storage interface controller you choose, every cable specification you lock in, and every infrastructure upgrade you delay shapes your future agility.

So, whether you are maintaining an SCSI disk array from 1998 or deploying an NVMe-oF cluster in 2025, remember that today’s “cutting edge” is tomorrow’s legacy system. Build wisely.

To receive swift and dependable assistance for all your computer parts requirements, call us at (855) 483-7810 or get in touch with our specialized team by completing a submission form.

Frequently Asked Questions

- What’s the main difference between SCSI and SATA?

SCSI was designed for multi-device, high-reliability environments (like servers), using shared buses, complex cabling, and advanced features like command queuing. SATA is simpler, cheaper, and connects one drive per port, perfect for consumer and general business use. SCSI evolved into SAS, which still competes with SATA in enterprise storage.

- Do people still use SCSI today?

Traditional parallel SCSI? Only in older industrial or medical systems does it occur. But its successor, Serial Attached SCSI (SAS), is very much alive in data centers that need high reliability and performance. Many organizations keep legacy SCSI gear running because it works, and replacement isn’t cost-effective.

- Why did SCSI need termination, and what went wrong without it?

Because SCSI used a shared parallel bus, electrical signals would reflect back without proper termination, causing data corruption or system crashes. Terminator plugs (active or passive) at both ends of the SCSI chain absorbed those signals.

Do you need advice on buying or selling hardware? Fill out the form and we will return.

Sales & Support

(855) 483-7810

We respond within 48 hours on all weekdays

Opening hours

Monday to thursday: 08.30-16.30

Friday: 08.30-15.30